Apr 12, 2020

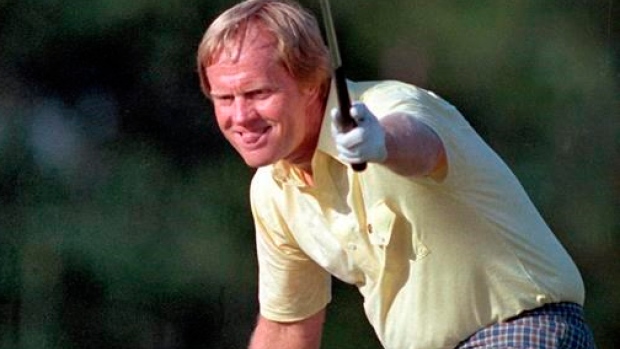

A look back at Nicklaus' 6th Green Jacket

Jack Nicklaus was down, playing poorly, and his pride was hurt. The unwelcome, hurting question kept coming: “When are you going to retire?” But it was a newspaper article which really enraged golf’s Golden Bear.

The Canadian Press

Jack Nicklaus was down, playing poorly, and his pride was hurt.

The unwelcome, hurting question kept coming: “When are you going to retire?”

But it was a newspaper article which really enraged golf’s Golden Bear.

“It said I was dead, washed up, through, with no chance whatsoever. I was sizzling. I kept thinking, ‘Dead, huh? Washed up, huh?’”

He answered with one of the great performances in golf’s long history, a stunning, thundering, magnificent rally that brought Nicklaus a record sixth Masters championship on Sunday.

In perhaps the finest hour of a career that is unmatched in golf, he won the 50th Masters by overcoming an international corps of the game’s finest players in a dramatic run over the final nine hilly holes at the Augusta National Golf Club, a stretch he played in a record-matching 30.

His round of 65 was highlighted by a 12-foot eagle putt on the 15th hole that pulled him within two shots of the lead. “I remember I had that same putt in ’75, and I didn’t read enough break,” he said.

He called on more than a quarter-century of experience, of winning and losing at the game he’s played with more success than any other man.

“This was Sunday at the Masters. There’s a lot of pressure. The other guys feel it, too. They can make mistakes. I knew that if I kept my composure down the stretch, as long as I kept on making birdies, as long as I kept myself in there, I’d be OK. I kept that right at the front of my mind,” he said.

And he was right.

Seve Ballesteros made a mistake. Tom Kite failed to take advantage of an opportunity. Greg Norman made a mistake that led to a bogey on the 72nd hole and cost him the tournament.

“I don’t like to win a golf tournament on somebody’s mistakes. But I’m tickled pink,” Nicklaus said. “Over the last few years, some people have done things, things I have no control over, that kept me from winning golf tournaments.

“This time a couple of guys were good to me and allowed me to win.”

The 46-year-old Nicklaus used the opportunity to answer the questions about retirement.

“I’m not going to quit. Maybe I should. Maybe I should say goodbye. Maybe that’d be the smart thing to do. But I’m not that smart.

“I’m not the player I was 10 or 15 years ago. But,” he added, with a grin, “I can still play a little bit at times.”

He was at his best on a hot, sunny spring Sunday when he turned back the clock with a 7-under-par 65.

“I didn’t expect to be in position to win, but I felt this morning if I shot a 66 I would tie, 65 I would win, and that’s exactly what happened,” Nicklaus said.

“I was doing things right. I finally made a bunch of putts. That’s what was fun. I haven’t had this much fun in six years.”

What had been a season of success for “no-name” players and misery for the game’s luminaries turned abruptly in the Masters. Five of golf’s biggest stars — Norman, Ballesteros, Bernhard Langer, Kite and Nicklaus — led or shared the lead at one point over the final 18 holes. In the end, it was the biggest name of all on top of the leader board.

“Fantastic,” he said. “You don’t win the Masters at age 46.”

But he did, for a record sixth time, to tie Harry Vardon, a six-time British Open champion, for the most victories in any of golf’s four majors, which also includes the U.S. Open and the PGA.

It pushed to 18 his record accumulation of victories in those events, five more than Walter Hagen. The list, which started with the 1962 U.S. Open, now includes the six Masters, a record-tying four U.S. Opens, a record-tying five PGA national championships, and three British Opens.

It also provided Nicklaus with his first major title since 1980 and his first victory of any kind since the 1984 Memorial tournament.

Norman, playing well behind Nicklaus, came surging up those final, hilly holes riding a string of four consecutive birdies that began on the 14th. When Norman dropped a putt of about 15 feet on the 17th — with Nicklaus’ round long finished and his 72-hole total of 279 on the board — Norman had achieved a tie for the lead at nine under par.

The powerful man known as “The Great White Shark” needed only a par on the 18th to tie and force a playoff. A birdie would win it.

But, with Nicklaus and his caddy-son Jack Jr. watching, Norman pushed his second shot into the gallery, and his sun-bleached head bowed in self-inflicted misery.

Norman pitched down the slope to 18-20 feet, then missed the par putt and Nicklaus was a winner again in one of the greatest golf tournaments of all time.

Norman had a closing 70 for a 280 total.

He was tied at that figure, a single stroke back, with Kite, the gutsy little man who has played so well so often on Augusta’s flowered hills yet always has come up empty.

Kite, too, had a chance to tie, but missed a 15-foot birdie putt on the 72nd hole, and crouched on the green, his hands covering his head, a portrait of despair. He had fired a brilliant 68 in a duel with Ballesteros, had once owned a share of the lead, yet was a loser again.

Kite and Norman were but two of the obstacles Nicklaus had to overcome.

At one time or another, Ballesteros was there, the dashing Spaniard who now, in the twilight of Nicklaus’ career, may be ready to assume the role of golf’s leader.

And there was Langer, the West German who was the defending champion; Corey Pavin, perhaps the best of America’s young stars; Tom Watson, the five-time British Open champion trying to win his third Masters; and Nick Price, the South African who set a Masters scoring record with a 63 the day before.

They were all there in contention at one time or another, all trying to beat Augusta National and their own nerves and, in the end, the man generally considered the finest player the game has ever known.

Ballesteros, who scored two eagles and, at one stage on the back nine, held a two-stroke lead, hit into the water on the 15th and eventually finished fourth with a 70 and a 281 total.

After making a birdie putt on the ninth hole, Nicklaus reached the turn in 35, one under for the day and three under for the tournament.

At that point, he was four off the pace with six men in front of him. But when he rolled in a 25-footer on the 10th, and another from about the same length on the 11th, the word began to spread from Amen Corner.

But a pulled tee shot on the threatening 12th led to a bogey and the attention again shifted to Ballesteros, Kite, Norman and Watson, who was making a small move.

Nicklaus, however, was undaunted.

A massive drive set up a mid-iron second shot to the par-5 13th and he two-putted for birdie.

“Where it really turned around was at 15. I had hit a big drive and I sat there with a 4-iron. I turned to Jackie and I said, ‘Do you think a 3 would go a long way here?’ And I took it an aimed it straight at the hole.”

He boldly lashed that iron shot toward the water-guarded green of the par-5 15th, rammed in a 12-foot eagle putt and looked gratefully to the heavens, a broad smile on his face.

Suddenly, he was seven under par for the tournament and in the hunt.

On the par-3 16th, he lofted his tee shot high against the backdrop of sky and pines. The ball touched down, then spun back. For a moment, it seemed he had made an ace. But the ball stopped about three feet away. He made the putt and was tied for the lead.

“It just kept building,” Nicklaus said. “We kept reading the putts right and I kept hitting them where I was looking, which is a very rare occurrence for me these days.”

He drove to the left on the 17th, then put his approach some 12-15 feet from the hole. He made the birdie putt and for the first time took the lead at nine under par.

He very nearly birdied the 18th, leaving a long-distance effort a couple of inches short. After he tapped in, he hugged his caddy son while the gallery yelled itself hoarse.

Then Nicklaus he could only sit and watch and wait as Norman played the 18th, first trying to beat him with a birdie, then trying to tie him with a par and eventually bowing with a bogey when his putt slid by.

And the Golden Bear — no longer called behind his back the Olden Bear — was a winner again.